- Home

- Yang Erche Namu

Leaving Mother Lake Page 13

Leaving Mother Lake Read online

Page 13

Añumo ate as though she had been starving, and I could not help commenting, “You eat like your father did the first time!” And Ama slapped me on the back of the head. I immediately understood why. Still, I kept staring at Añumo because the Yi have a very peculiar way of eating by placing food in their cheeks while they still are taking more into their mouths, until their cheeks seem very full and round like squirrels’ cheeks. When she had finished eating, she came into my room and we went to sleep next to each other. She fell asleep right away because she was so tired. I too was very tired, but I found it difficult to sleep. First of all because the events of the night had disturbed me, and then because of the acrid smell that emanated from Añumo’s hair. Following the custom of her people, my blood sister had not washed her hair or her face for a very long time.

When she joined us for breakfast the next morning, I had already warmed up the water to wash her hair. Before she had a chance to sit and drink a bowl of tea, I handed her the washbasin. “Here, come outside with me and let me wash your hair. I could not sleep all night.”

This time my mother did not slap me. Añumo was horribly embarrassed but she obliged me and followed me into the courtyard carrying our enamel basin. When I had finished drying her hair with the toweling cloth, my Ama said, “You have such long and silky hair, Añumo. Would you like me to comb it for you?”

Añumo smiled and my mother combed her beautiful hair and braided it into two parts as was the correct way for a married woman. Then Ama carefully cleaned her comb, placing the loose hair in the little basket under the porch with the rest of our hair, because we believe that unless we store every loose strand of hair, the birds will use them to make their nests and give us headaches.

Later in the morning, when I picked up my basket to go and do some weeding in the fields, Añumo prepared to come with me but my mother would not let her go because of her foot. “You can’t go anywhere with this,” she told her. “And you need to rest. You have a long way to run before you get back to your father’s house.”

When I came back from the fields sometime after noon, Añumo was standing at the stove, working side by side with my mother. They were making tofu and taking turns at stirring and scooping the thick white foam rising above the bean stew. I could not help thinking that they looked like mother and daughter, and again I felt so sorry that Añumo was not a real sister to me. I did not want her to leave, and told her as much.

“But I can’t stay with you, Namu,” she said a little sadly. “I’m a married woman. What would my husband say? And my father?”

“Well, if you stay here with us, you won’t have to worry about husbands or fathers, will you?”

Añumo held her breath for a while and then she burst out laughing. For my part, I did not think it was very funny, and I continued arguing, trying to convince her to stay with us, until the dog cut the discussion short, barking furiously. And just as my mother went out to see what was happening, Zhema rushed into the room and went straight to the pantry. “Quick, Namu, they’re here! She has to run,” she ordered in a low voice, as she took out some barley cookies and quickly cut a thick slice of ham, which she wrapped in a cloth.

Añumo had sprung to her feet, ready to run, but she did not know which way to escape and so she stood in the middle of the room, her eyes wild and darting toward every corner, like a trapped animal.

“Wait! At least put the shoes on properly. Be careful of your foot,” I pleaded, my voice breaking and my eyes burning.

She looked down at her feet and bent over to pull the canvas shoes over her heels, and I helped her tie the laces. Meanwhile, Zhema had grabbed her felt cape and wrapped it around her shoulders. She pushed the food into her arms and, taking her by the hand, quickly led her through the storeroom and out of the house and into the vegetable garden, where we helped her over the mud wall.

The men, a party of six, had come into the courtyard, and my mother was talking with them, doing her best to waste their time. “Yes, she must be quite a long way away by now. She left yesterday. But you must be so tired, why don’t you stay for dinner and sleep here overnight?”

The men looked at each other and hesitated. They were very tired and they could do with something to drink. So they came into our house and wasted more time, but they would not stay for dinner.

After they left, I suddenly felt angry at my mother. “Why didn’t you say something to them? Why didn’t you keep them here longer? Why didn’t we keep her here? You’re an older woman, the men would listen to you!”

My mother shook her head impatiently. “This is a Yi custom. She has to run back home. What are you so upset about?”

Well, I knew it was a Yi custom, but Añumo was my sister, and I knew better than anyone how dangerous the mountain was and how late in the afternoon already, and I could not bear to think of how frightening it must be to run alone through the night. I was far from knowing then that only a few months from now, I too would be running alone in the mountains.

Meanwhile, from that evening on, whenever I heard a dog barking in the night, I no longer feared that a man might be coming to knock at my window. Instead, I hoped it was Añumo returning to stay with us after all. But we never saw her again.

A Song and a Trip to the City

Not long after Añumo left us, we received other visitors. I had been at the lakeshore all day with my girlfriends, turning over the earth to prepare for the spring planting. And now the sun was beginning its descent behind the mountain and the birds were growing quiet. It was time to walk home. We were almost at the village when we heard the children laughing and calling out: “Letsesei! Guests are coming! Letsesei!”

Outsiders were so rare. Except for government officials and the paramedics who chased after the children with vacci-nation needles, no one ever came to our village. In those days the only motor vehicles that crossed our mountains were the log trucks that sputtered up the hills and then rolled down the dirt tracks, freewheeling over potholes, their engines cut off to save fuel. But even these dirt tracks were a long way from Zuosuo. To get to our village, you had to come on foot or on horseback.

Before we even saw their faces, just from the way they held the leads of their horses, we knew that only one of the four guests was Moso. When we met up with them, we recognized our neighbor Yisso, a big man with a thick head of black wavy hair and laughing eyes. As for the three Han Chinese, we had never seen them before. One was quite old, with white hair, and evidently the leader, because he was doing most of the talking.

“Ni hao!” the children called out in the few Chinese words they had managed to acquire at the local school.

“Ni hao! Ni hao,” the officials answered, with big kindly smiles on their faces.

Being grown women, we only looked and nodded our heads and pretended not to be excited, but we followed them for a little while down the path until we had made sure that they were going to Yisso’s house. When we turned back, we could not contain our curiosity. “Maybe they’re surveyors,” Erchema said. “Do you remember the surveyors who brought all that candy?”

“Well, I hope these guests have brought some candy too,” I joined in emphatically, because I had never eaten candy wrapped in paper, and because I didn’t remember the surveyors who had come when I was still living with Uncle in the mountains.

The news that there were guests staying at Yisso’s house spread from door to door like wildfire, and before we had sat down for dinner, we had already found out that they were not surveyors but cadres from the Cultural Bureau in Yanyuan county who had come to record Moso songs. We also knew their names. The leader, the old man with the white hair, was Mr. Li. The younger ones were Zhang and Zhu, though we were not sure as yet which was Zhang and which was Zhu.

“They heard that our village has the best singers,” Dujema said with unrestrained pride.

And I thought, Yes, that’s true, we have Latsoma and Zhatsonamu, and I can sing louder than anyone else. I asked Ama, “Why don’t they come here to

stay with us? Why do they have to stay with Yisso?”

“Yisso speaks Chinese,” she replied rather gruffly. Then she muttered, “What use can Moso songs be to the Han anyway?”

My Ama was stirring a big pot of stew. There was a deep scowl in the middle of her forehead and her mouth was all tight. She was in a bad mood because Zhema had come home late to help with the dinner and because, since the Cultural Revolution, nobody in our village ever felt very enthusiastic about Han officials, even if all they wanted was to collect our songs.

Nonetheless, over the next two days, whatever their mothers and uncles thought about Han officials, the children followed Mr. Li and Zhang and Zhu everywhere, running back and forth from house to house to give the latest news. As for us, the young people, we gave up our work in the fields and listened to the children’s every word.

The first morning, Yisso had taken the Han by canoe to the island of Lewube and they had climbed up the hill to visit the little Buddhist temple that had escaped the Red Guards’ fury. There, standing under heaven, the Han had squinted in the bright sunlight and turned in every direction, pointing above the lake toward Gamu Mountain and then beyond the jagged horizon to places of interest to them. “Kunming is in this direction!” “No, no! It’s over there!” “Aya! Over there is Chengdu!” In the afternoon the Han had gone to Zhatsonamu’s house and she had sung the goddess song for them. And in the evening, the Han had tea with old Guso. There was a big crowd of people in the house, and Guso was telling the story of the rabbit who got the better of the tiger. Of course Yisso was translating! How else could the Han know what he was saying? On the second morning, a little boy called out, “I saw the guests suck on little brushes and foam at the mouth!” This time I could no longer repress my curiosity; I had to run after him to see for myself. I had never seen anyone brushing his teeth.

In the afternoon the children ran ahead of Yisso and the cadres from the Cultural Bureau, who were making their way to our house.

“They’re here!” Homi ran in to tell my Ama. “They’re in the courtyard!”

My Ama wiped her hands on her trousers and glared from behind the cooking stove toward the front door, where Yisso and the guests were stepping through, squinting in the darkness and stumbling on the dog, who sprang out of their way after nipping Mr. Zhu on the leg. I shooed the dog outside.

“It’s nothing, it’s nothing. Don’t worry!” Mr. Li said to me while Mr. Zhu rubbed his leg.

Mr. Li had brought us a pack of tailored cigarettes, brick tea, and rice wine, and my mother, seeing that these people knew the proper way to behave, at last softened her stance, and placed their gifts on the ancestors’ altar.

Soon we were all sitting at the fireplace, Zhu still tapping his leg and the others brushing the dust off their trousers, then peeling their apples with a knife in Han fashion, and drinking black tea because no one expected Han Chinese to like butter tea. Zhang had tried to entice Jiama and Homi and the other children to play, but they were too shy. When he went to touch them, they giggled and twisted their bodies sideways, and suddenly they shrieked and ran outside looking for their mothers. Jiama then grabbed hold of Ama’s vest and Homi took my hand.

Meanwhile, Mr. Li had explained to my mother that he wished to hear as many people sing as possible and that he wanted to organize a big dance in someone’s courtyard. To my delight, Ama answered, “We can do it here.” And when Yisso suggested bringing more firewood for the bonfire, she said firmly, “No need, we have enough.”

I could have jumped for joy, but instead I asked Yisso, “Do they have any candy wrapped in paper?”

Ama turned about and fired an astonished look in my direction. Pulling me to her side, she said sternly, “Namu, come and help me over here!” “Over here” was in the courtyard. “Where have you learned to beg from guests? You’re a grown woman! Just as well they can’t understand what you’re saying!”

That evening the villagers made their way to our house, bearing pine torches to light their path. The Han were already standing near the bonfire, talking among themselves, Mr. Li looking like a leader, Zhang holding a black plastic box, while Zhu, who had evidently got over the dog bite, was demonstrating a dance step. As the villagers walked into the courtyard, Mr. Li and Zhang and Zhu bared their brushed teeth, smiling from ear to ear, calling out, “Welcome! Welcome!” in Chinese. And soon we were all standing in a tight circle around the fire — watching with wide-open eyes, feeling much too curious to have anything to say, until an old woman commented between two drags on her clay pipe, “You wonder how they can ride horses with those flat butts,” and everybody laughed.

Zhang put the black box on the ground, and Yisso translated that Mr. Li wished to hear all of us sing and that someone had to start. Now, among our people, if you can walk you can dance, and if you can dance you can sing, so we were not short of singers. But we thought that, to begin with, they should hear someone special, so we turned to Achimi because she was an old lady and she could sing about our old stories. Jiaci accompanied her on the bamboo flute and Achimi sang a sad and hopeful song about saying good-bye to the horsemen who were taking the caravan to Tibet. After Achimi, women and men of all ages stepped into the circle, one after the other. I followed my friend Erchema. When all those who wanted to sing had had a turn, we waited to be told what to do next, all the while watching Mr. Li’s every move and trying to guess what he was saying to the others. Then Zhang nodded his head and pressed on the black box, and we heard Jiaci’s flute and Achimi’s voice coming out of the box.

“Ah! What is this thing?” the people shouted. “What is this black box?” And they moved as one body toward the box.

“Don’t push! Don’t push!” Mr. Li cried.

“Do that again!” the people answered. “Touch that box again!”

So Zhang touched the box, and when Jiaci again heard himself play, he said: “This box learns very fast, it only listened to me once and now it can already do it!” Everyone laughed. Yisso translated for the Han and they laughed too. Then he turned to the rest of us and spoke in the superior tone of one who has traveled the world. “It’s called a tape recorder,” he said, using the Chinese word. “These things are made in Japan.”

“Where’s Japan?” someone asked.

There was a pause. For aside from Dr. Rock, who was a ghost from a fabled country called America, our people knew only two types of foreigners: the English, who were in India and Tibet, and the Japanese, who had made war on China. But no one had ever bothered to think of where Japan was.

So Yisso spoke up again. “Japan is an island in the east.” And old Guso, who could not take his eyes off the tape recorder, shook his head. “Well, that’s no good. You can’t ride a horse to an island.” And again everybody laughed.

For the rest of the evening, we sang and the Han recorded our songs and then played them back to us until, very late in the night, the tape recorder began emitting whiny tremolos and Mr. Li explained that he wanted to save the rest of his batteries for the next day. Besides, he and his colleagues were very tired. So we wished them a peaceful night and watched them disappear behind Yisso, who was carrying the wondrous tape recorder under his arm. We did not move. We sat around the fire talking about the black box for a long time.

THE HAN STAYED THREE DAYS . On their last afternoon, Yisso once again brought them to our house. They had something important to discuss with my mother — Mr. Li wanted to take me back with him to Yanyuan to take part in a singing contest. He had chosen three of us; the other two were our best singers, Latsoma and Zhatsonamu. Mr. Li would take care of all our expenses and “if the girls win a prize, they will bring back a little money.” And above everything else, of course, if we won a prize, we would bring fame to our village and our Moso people. And yes, Mr. Li was quite sure that we were good enough to win a prize. Did my mother agree to let me go?

At first I could not believe it. But as Yisso kept on talking and my sister Zhema and my friend Erchema and the others turn

ed toward me, smiling with admiration and a little envy, I had to trust that I was not just wishing for this but that it really was happening — I was going to travel with Latsoma and Zhatsonamu to the city; we were going to take part in a singing contest in Yanyuan, and Yisso would accompany us because we did not speak Chinese and we were very young and we knew nothing about the world. Now, I had no idea why anyone would want to sing Moso songs in the city, but just the same I was overjoyed. Ever since I had gone to live with Uncle, I had watched the birds fly over the mountain peaks and wondered what lay beyond. I had watched the horsemen with the caravans and I had listened to their stories about the world outside. And now it was my turn. I was going to see the world. I was going to see all the marvels the men talked about. I was going to see the cars and the trucks and the movies and the airplanes. I was going to see the “oil road” that was so slick and shiny, Zhema’s lover had once told me, you could admire your reflection in it.

Over the next few hours, I grew every bit as impatient as when I had said good-bye to Uncle. In the meantime, my mother dispatched my sister to the neighbors to borrow the things I needed for the trip, and soon they had assembled three different outfits in beautiful bright colors, with matching jewelry. My Ama said, “When you leave your home, you must look your best, you don’t want your people to lose face. And remember the old proverb ‘There are no white eagles, and there are no good Han people.’ So don’t leave the other girls. You must stay together wherever you go. You must be just like eyes and eyebrows!”

Zhema added, “Yes, you must be like the fingers of one hand! Inseparable. And please, make sure you bring me back some white socks.”

The village girls also wished for something: “Can you bring us some scarves?” And they handed me a box of wild mushrooms to trade for their goods.

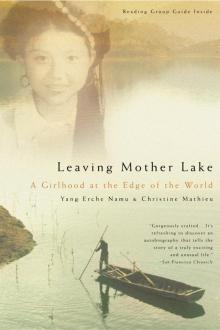

Leaving Mother Lake

Leaving Mother Lake